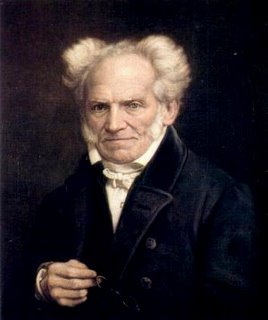

First of all i would like to say if i ever find myself capable of such facial hair i must have it. Secondly, read this excerpt of Nietsche's Seond Essay of The

Genealogy of Morals with your 'purpose of life' in mind. Does bad conscience propel you? If so how? Also, realize that Nietzsche believes our current system of values to be incorrect, he is not arguing within the popular moral beliefs.

At this point I can no longer avoid giving a first, provisional statement of my own hypothesis concerning the origin of the "bad conscience": it may sound rather strange and needs to be pondered, lived with, and slept on for a long time. I regard the bad conscience as

the serious illness that man was bound to contract under the stress of the most

fundamental change he ever experienced—that change which occurred when he found himself finally

enclosed within the walls of society and of peace. The situation that faced sea animals when they were compelled to become land animals or perish was the same as that which faced these semi-animals, well adapted to the wilderness, to war, to prowling, to adventure: suddenly all their

instincts were disvalued and "suspended." From now on they had to walk on their feet and "bear themselves" whereas hitherto they had been borne by the water: a dreadful heaviness lay upon them. They felt unable to cope with the simplest undertakings; in this new world they no longer possessed their former guides, their regulating, unconscious and infallible drives:

they were reduced to thinking, inferring, reckoning, coordinating cause and effect, these unfortunate creatures; they were reduced to their "

consciousness," their

weakest and

most fallible organ! I believe there has never been such a feeling of misery on earth, such a leaden discomfort and at the same time the old instincts had not suddenly ceased to make their usual demands. Only it was hardly or rarely possible to humor them: as a rule they had to seek new and, as it were, subterranean gratifications.

All instincts that do not discharge themselves outwardly turn inward—this is what I call the internalization [Verinnerlichung] of man: thus it was that man first developed what was later called his "soul." The entire inner world, originally as thin as if it were stretched between two membranes, expanded and extended itself, acquired depth, breadth, and height, in the same measure as outward discharge was inhibited. Those fearful bulwarks with which the political organization protected itself against

the old instincts of freedom—punishments belong among these bulwarks—brought about that all those instincts of wild, free, prowling man turned

backward against man himself.

Hostility,

cruelty,

joy in persecuting,

in attacking,

in change,

in destruction—all this turned against

the possessors of such instincts: that is the origin of the "bad conscience."